PALM TREE PRODUCTIONS

Operation Lifeline Sudan 1989-1993

This is not an official statement of the United Nations or any associated organization.It is a personal account of situations and initiatives by Detlef Palm while working as programme coordinator for OLS

You may also view the entire story as as an album: click here.

Operation Lifeline Sudan, or OLS, was during its first few years the largest humanitarian relief operation at the time. It was an affiliation of several UN-agencies and circa 40 non-governmental organizations (NGOs), providing humanitarian assistance to the war- afflicted people in southern Sudan, and operating under a common framework and agreements. The long-lasting conflict between the Sudan People's Liberation Army and the government of Sudan had reached a new height. The SPLA forces controlled huge swaths of land, while the government controlled the major garrison towns. Virtually all of the civilian population, half of them children were cut off from any assistance from government or the humanitarian community in Khartoum.

South Sudan is an area challenging for those who live there and for those trying to help. Much of the life in southern Sudan is connected to the rivers which flood vast tracks of land in one season, and dry up in the next. South Sudan can be a swamp at one time, and a desert at another.

Perhaps

all started with this planeload of UNIMIX (a ready-made porridge for

malnourished children) delivered with our UNICEF Twinotter to Abiye,

in late 1988. Many Southerners had come to Abiye, which belongs to

the northern province of Southern Kordofan, in need of assistance.

The misery of the several thousand people who made it to Abiye, made

it clear that an enormous disaster was looming in southern

provinces, and that these people could not be reached through

assistance to the government held towns.

Perhaps

all started with this planeload of UNIMIX (a ready-made porridge for

malnourished children) delivered with our UNICEF Twinotter to Abiye,

in late 1988. Many Southerners had come to Abiye, which belongs to

the northern province of Southern Kordofan, in need of assistance.

The misery of the several thousand people who made it to Abiye, made

it clear that an enormous disaster was looming in southern

provinces, and that these people could not be reached through

assistance to the government held towns.

It took several weeks of planning, research, and negotiations, both with the SPLA and the government, to reach agreement for a cross-border relief operation into south Sudan. "Cross-border" meant that relief to civilians living in SPLA-held areas would be provided from Kenya, across-the-border, without routing it through Khartoum or other government held territory.

One of the first programmes supported by UNICEF were immunization campaigns for children. Most children in southern Sudan had not had the benefit of health services since they were born, and were never vaccinated. Mortality from measles, especially if combined with malnutrition can be very high.

Vaccination stations were set up everywhere one could go, and local personnel trained. Even campaign-style media materials were produced and distributed. The logistics of building up a cold chain for temperature-sensitive vaccines were enormous.

Above are snapshots from those waiting to be immunized, or their children to be immunized: Murle people in the first and second picture, a Dinka lady carrying her twins in goat hides, and an Uduk mother carrying her child in a special contraption.

Life

was tough for the relief workers in South Sudan. Some of them stayed

and lived in tents for years. Left is the outdoor kitchen of a

relief camp near Torit. On the right, one of the storage tents at

the forwarding base in Lokichogio. Once an unknown village in the

north-western-most corner of Kenya, it quickly became one of the

busiest airstrips in East Africa. It also became the most important

transit stop for virtually all relief workers, both from the UN and

from NGOs, as well as a place for those in need of some rest and

recuperation after having spent some weeks in southern Sudan. That

didn't mean that the Lokichogio camp - that time entirely run by the

UN - was a safe and pretty place.

Life

was tough for the relief workers in South Sudan. Some of them stayed

and lived in tents for years. Left is the outdoor kitchen of a

relief camp near Torit. On the right, one of the storage tents at

the forwarding base in Lokichogio. Once an unknown village in the

north-western-most corner of Kenya, it quickly became one of the

busiest airstrips in East Africa. It also became the most important

transit stop for virtually all relief workers, both from the UN and

from NGOs, as well as a place for those in need of some rest and

recuperation after having spent some weeks in southern Sudan. That

didn't mean that the Lokichogio camp - that time entirely run by the

UN - was a safe and pretty place.

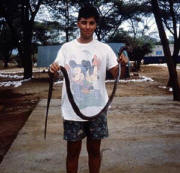

On

the left is Adrian Pintos (a veterinarian) with a black mamba found

and killed in one of the base camp tents.

On

the left is Adrian Pintos (a veterinarian) with a black mamba found

and killed in one of the base camp tents.

The idea was, of course, to travel as far as possible overland, to

avoid costly air transport. This led quickly to many precarious

situations. Here a river-crossing between Kapoeta and Torit.

And sometimes it just wouldn't go any further. And the local people right across the border, from the Toposa tribe, did not induce a particular homey feeling among the foreign relief workers...They were always friendly to the foreigners, but engaged in fierce battle and cattle raids with the Turkana people, right in Lokichogio.

One had to resort to flying. By mid 1993, there were about 18 aircrafts chartered for OLS, connecting as often as possible with a little less than 40 locations in southern Sudan. The fleet included the smallest plane, normally used for rescue landings on glaciers in the Swiss mountains, up to several Hercules ex-military aircraft, with a payload of 20 metric tons. Not all aircraft could land everywhere - the smaller planes were used to shuttle people or light-weight supplies such as vaccines and medicines, the larger one usually carried food supplies for WFP. While 20 metric tons sound quite a lot, they don't look much once stowed in the aircraft. On the right, I am accompanying an even smaller load in a Buffalo - which looks like there was room for twice as much. One of the first major reunification of child soldiers with their families was also carried out by Buffalo aircraft - no seats required.

Flying in Sudan was no joke. The first reconnaissance flights often

went into new locations without any ground contact, and without

knowing whether one would be welcome or not. It was wise to sit on

bullet proof cushions. There would be nobody to chase animals from

the airstrip - or whatever had been left over from an airstrip after

years of abandon. Some airstrips looked distinctly banana-shaped.

Once an aircraft returned home to Lokichogio with bullet holes in

its tail, though no aircraft was shot down, as had tragically

happened over Aweil with an aircraft starting from Khartoum. But we

lost a Cessna, too - the mud of Akobo wouldn't let it go when it

tried to take-off.

Flying in Sudan was no joke. The first reconnaissance flights often

went into new locations without any ground contact, and without

knowing whether one would be welcome or not. It was wise to sit on

bullet proof cushions. There would be nobody to chase animals from

the airstrip - or whatever had been left over from an airstrip after

years of abandon. Some airstrips looked distinctly banana-shaped.

Once an aircraft returned home to Lokichogio with bullet holes in

its tail, though no aircraft was shot down, as had tragically

happened over Aweil with an aircraft starting from Khartoum. But we

lost a Cessna, too - the mud of Akobo wouldn't let it go when it

tried to take-off.

Cattle are the livelihood of the people of south Sudan, regardless

their ethnicity. Cattle are the people's wealth and pride. Cattle

are revered, and protected. Men and children in the cattle camps may

live for weeks from the milk. Cattle are rarely slaughtered (though

I have seen meat being sold).

Cattle are the livelihood of the people of south Sudan, regardless

their ethnicity. Cattle are the people's wealth and pride. Cattle

are revered, and protected. Men and children in the cattle camps may

live for weeks from the milk. Cattle are rarely slaughtered (though

I have seen meat being sold).

Cattle became important for our work: Young children typically live

in the cattle camps. On the right, you see a "Dinka dairy" - a tree

in the middle of a cattle camp with all the milk

containers, with a

young child sitting underneath. But while some groups were not

particularly keen on having their children vaccinated, they were all

for having their cattle

containers, with a

young child sitting underneath. But while some groups were not

particularly keen on having their children vaccinated, they were all

for having their cattle

vaccinated against Rinderpest. South Sudan

has been one of the last great reservoirs of Rinderpest, and most

surrounding countries had successfully "cordoned off" Rinderpest

through vaccinating programmes. Here we had the opportunity to help

protecting the Southerners' cattle against the deadly and highly

contagious disease, and to reach the young children living in the

camps for vaccination against the childhood killer diseases.

vaccinated against Rinderpest. South Sudan

has been one of the last great reservoirs of Rinderpest, and most

surrounding countries had successfully "cordoned off" Rinderpest

through vaccinating programmes. Here we had the opportunity to help

protecting the Southerners' cattle against the deadly and highly

contagious disease, and to reach the young children living in the

camps for vaccination against the childhood killer diseases.

Started by the Red Cross, UNICEF took over the cattle vaccination programme in southern Sudan. Less than 4 years into the programme, 4 million cattle had been vaccinated. The Livelihood of many thousand families had been strengthened, and many thousand children were protected against measles, polio, and other childhood illnesses.

And if you behaved well, you had the chance to be invited to a Dinka-meal of milk and porridge...

Water, potable water, another prerequisite for survival. Years of

war and neglect had rendered most previous water-systems broken.

Here, a hand pump near Torit, not functioning, as can be seen by the

growing grass were normally people would queue to wait for their

turn. There were a wide range of different pumps previously

installed, by different aid agencies or local governments - which

didn't make the repair work easier. At the far right, repair men at

work, South Sudan-style. Next right, a diesel powered system in

Akobo, with a shiny new pump driving the deep well rig.

Water, potable water, another prerequisite for survival. Years of

war and neglect had rendered most previous water-systems broken.

Here, a hand pump near Torit, not functioning, as can be seen by the

growing grass were normally people would queue to wait for their

turn. There were a wide range of different pumps previously

installed, by different aid agencies or local governments - which

didn't make the repair work easier. At the far right, repair men at

work, South Sudan-style. Next right, a diesel powered system in

Akobo, with a shiny new pump driving the deep well rig.

Food remained a paramount concern in all the years. Food

self-sufficiency, as much as it could be possible, was a key

concern. Provision of seeds and agricultural tools, such as hoes and

machetes, became a major part of the programme. One kilogram of

seeds delivered and planned, would save 30 - to 60 kilograms of food

that would need to be provided later as relief. Left a garden

nursery for a settled community such as in Torit. Right,

distribution of spades and machetes, and the agricultural

coordinator proudly showing off the maize planted from relief seeds.

Food remained a paramount concern in all the years. Food

self-sufficiency, as much as it could be possible, was a key

concern. Provision of seeds and agricultural tools, such as hoes and

machetes, became a major part of the programme. One kilogram of

seeds delivered and planned, would save 30 - to 60 kilograms of food

that would need to be provided later as relief. Left a garden

nursery for a settled community such as in Torit. Right,

distribution of spades and machetes, and the agricultural

coordinator proudly showing off the maize planted from relief seeds.

Of course, it's not all that easy. Distribution of goods often

defied western rationale. For instance, as we supplied seeds and

tools, the local elders or authorities would give them to the better

off people and not - as suggested by us - to those who were left

with nothing. The better off are the better farmers, the chief

argued, and they should grow. Come harvest time they would share and

ensure that everyone gets. ...There were pests, such as the locust

seen here, but worse were the droughts that happened in those years.

Of course, it's not all that easy. Distribution of goods often

defied western rationale. For instance, as we supplied seeds and

tools, the local elders or authorities would give them to the better

off people and not - as suggested by us - to those who were left

with nothing. The better off are the better farmers, the chief

argued, and they should grow. Come harvest time they would share and

ensure that everyone gets. ...There were pests, such as the locust

seen here, but worse were the droughts that happened in those years.

So we were using sophisticated remote sensing data obtained from

satellite imaging, to project plant growth and success and failures

of harvests, and the possible need for food relief. In most

countries, there is no need to pay such close attention - because a

shortfall in food in one year can be compensated through purchases

using savings from the last year, or merely through market

mechanisms. In southern Sudan there was no market, there was no

transport infrastructure that would allow a market, nor was there

security, nor was there money. Forecasting, early alerts, and good

planning was key to avert major stress, if not starvation. The

colorful picture to the left shows the NDVI, or normalized

So we were using sophisticated remote sensing data obtained from

satellite imaging, to project plant growth and success and failures

of harvests, and the possible need for food relief. In most

countries, there is no need to pay such close attention - because a

shortfall in food in one year can be compensated through purchases

using savings from the last year, or merely through market

mechanisms. In southern Sudan there was no market, there was no

transport infrastructure that would allow a market, nor was there

security, nor was there money. Forecasting, early alerts, and good

planning was key to avert major stress, if not starvation. The

colorful picture to the left shows the NDVI, or normalized

difference vegetation index, which is a rough indicator of the

biomass measured from a satellite. The picture shows a yellow and

red band stretching roughly from Northern Kenya, Kapoeta to Malakal

and widening over northern Sudan (of which very much is desert). The

yellow/red area does not produce much vegetation. Likewise, the

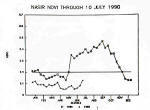

white chart indicates, for the location of Nasir, that the

vegetation index in the current year (the incomplete graph) is much

lower than it was in the previous year - another indication for a

drought.

difference vegetation index, which is a rough indicator of the

biomass measured from a satellite. The picture shows a yellow and

red band stretching roughly from Northern Kenya, Kapoeta to Malakal

and widening over northern Sudan (of which very much is desert). The

yellow/red area does not produce much vegetation. Likewise, the

white chart indicates, for the location of Nasir, that the

vegetation index in the current year (the incomplete graph) is much

lower than it was in the previous year - another indication for a

drought.

But there is more food than meat, milk and sorghum. One of the very successful interventions was the provision of fishing lines and hooks. Fishing twine, used to make nets, is not cheap. When delivered to the people, it wouldn't take long to see them turned into nets and put to use. Many of us became experts in appraising the thickness of fishing twine and the size and shapes of hooks. But nets also need to be cast from the river, and people have to cross rivers with their belongings. We found that many of the traditional canoes, made from trees in the Ethiopian highlands, were gone: stolen by the militia or the army, or sunk. Here a picture from Nasir and the Sobat River: No tree in sight to cut for a canoe. UNICEF had canoes manufactured from fiberglass for villages. Also in the picture a rubber craft used by the relief workers for food distribution and general transportation.

When I visited remote villages along the river for the first time (such as Abwong, pictured left), I got offered nothing else than fish, for breakfast, lunch and dinner. An acquired taste, but life-saving.

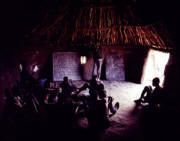

Is education a serious relief intervention, a life saving measure? Absolutely. For children who have nothing else seen than war, violence, destruction and chaos, education offers the sensible choice. The hunger for education among the children of southern Sudan was unbelievable. They would come to class, even if the classroom had no roof. They would sit under trees, or in the wide open space, without shade, to listen to their teachers. They might have had no clothes, but they wanted to learn. Parents were ready to invest in building simple structures, where this was possible.

Above a boy, proudly showing his math works, in an exercise book cut into half, so everyone had one. We supplied enough exercise books that this wouldn't have been necessary, but it reflects well a fear that supplies might run out soon again.

Above the boys called "minors" (meaning unaccompanied minors), young boys who were thought to be army recruits with or against their will. Many of them were later transferred from their training camps to Kenya into a transition camp, and many others were re-united with their families straight from where they were found. Tracing and reunifying these young boys was often done in cooperation with the ICRC; these programmes also were the forerunners of what later became "protection programmes".

Nasir, at the Sobat River, was one of the larger relief sites

serviced from Lokichogio. OLS occupied the only remaining building

in town, a riverfront property seen on the left. It served as

office, as kitchen, as mess and recreational room (people preferred

to sleep in their tents during the night). John White, on the right,

way over 60 years of age and undisputedly the oldest of us all,

cheerfully puts the buildings to use.

The airfield was good enough for a small aircraft, such as our

TwinOtter, during the dry season. When the rains started, our teams

reinforced the landing strip with bricks and rubble from the

dilapidated buildings in the town. Not quite what you might expect,

but it worked well for our light planes. Below the airstrip,

offloading stuff from the TwinOtter, and relief workers on their way

to work.

The airfield was good enough for a small aircraft, such as our

TwinOtter, during the dry season. When the rains started, our teams

reinforced the landing strip with bricks and rubble from the

dilapidated buildings in the town. Not quite what you might expect,

but it worked well for our light planes. Below the airstrip,

offloading stuff from the TwinOtter, and relief workers on their way

to work.

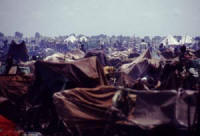

The disaster hit when due to a change in government in neighboring

Ethipia, refugee camps were dissolved and thousands and thousands of

returning Sudanese came down the Sobat River and poured into Nasir.

They had nothing. Somehow their trek stopped. The SPLA militia,

having lost their re-supply base in Ethiopia, played tricks with the

refugee's presence. The crowding was unbelievable. People slept in

grass-huts, exposed to the weather day and night, and resorted to

eating snails and worms.

The disaster hit when due to a change in government in neighboring

Ethipia, refugee camps were dissolved and thousands and thousands of

returning Sudanese came down the Sobat River and poured into Nasir.

They had nothing. Somehow their trek stopped. The SPLA militia,

having lost their re-supply base in Ethiopia, played tricks with the

refugee's presence. The crowding was unbelievable. People slept in

grass-huts, exposed to the weather day and night, and resorted to

eating snails and worms.

The UN mounted an immediate airlift. The food had to be dropped from the aircraft, because there was no landing space at the Sobat River. An Airdrop is not fun. It is dangerous for the crew and aircraft, when the load suddenly rolls out of the plane and shifts the balance. It is dangerous for those trying to help, because the food scatters around a vast area. Food get dropped into the swamps, the river, or – as it sometimes appeared to be the case - just disappeared forever into the ground, on impact. Recovery rates of 90% were considered to be very good. In the series below, the Hercules C130 aircraft approaches. The tailgate opens. The palettes with food, a total of 20 tons at a time, are being dropped.

In the next three pictures, the food is hitting the ground, sounding like shells pounding. The next picture shows the bags of food after collection. All bags get triple-packed, to minimize losses. Finally, food is loaded into rubber craft for distribution along the river.

First, things seem to be fairly wellunder control. Many families returning from the refugee camps in Ethiopia had build up good nutrition, and even some goods to barter for food, as the need arose.

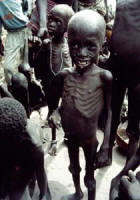

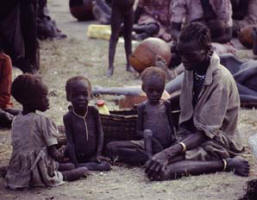

A few weeks later, things spun out of control. People died. Children died. Relief workers died. Mass starvation struck in a giant scale, first in what became known as the hunger-triangle. This was the area between Waat, Ayod and Kongor. People appeared out of the nowhere, emaciated and without food for several weeks. Nobody had known where they had been. They simply had been off the radar of the humanitarian community, in spite of relief workers visiting every little village in Sudan where we were told that people lived and were in need.

People who starved were not buried, so as not to weaken those who still lived. The war continued in full scale, now with inter-factional fighting, between ruthless war lords inflicting raids, terror and fear among the population. Who could tell whether what was distributed as "dry ration" during the day was not taken away from the women at night. Feeding centers with supplementary and therapeutic food for children were run by the UN and NGOs, but still children died who came too late. Later, the nutrition crisis extended to the southern part of south Sudan. In the turmoil, four relief workers were murdered.

The hunger was so bad, that old men and young children would come to the aircrafts offloading food (like here in Ayod) to pick up individual grains that dropped from cracked bags into the sand.

Times have changed since then. There is a peace in southern Sudan. It is possible that poverty creates war, but it is more likely that war creates poverty. Especially among those who are already vulnerable, marginalized and deprived.